Financing deep energy renovation: leveraging the Just Transition Mechanism and carbon revenues

Calculating the actual cost of renovating 97% of the existing building stock in the EU is no easy task. Various methodologies have been applied, each being met with both applause and critiques. Generally, a realistic number seems to be in excess of €300 bn per year for the next 30 years. To drive that number home, it’s helpful to think of this way: ~€1 bn per day, every day until 2050.

While that is a lot, it is worth noting that the International Energy Agency estimates that aggressively implementing energy efficiency on a global scale could – by slashing energy bills, reducing energy imports and alleviating energy poverty – deliver benefits of €500 bn per year.

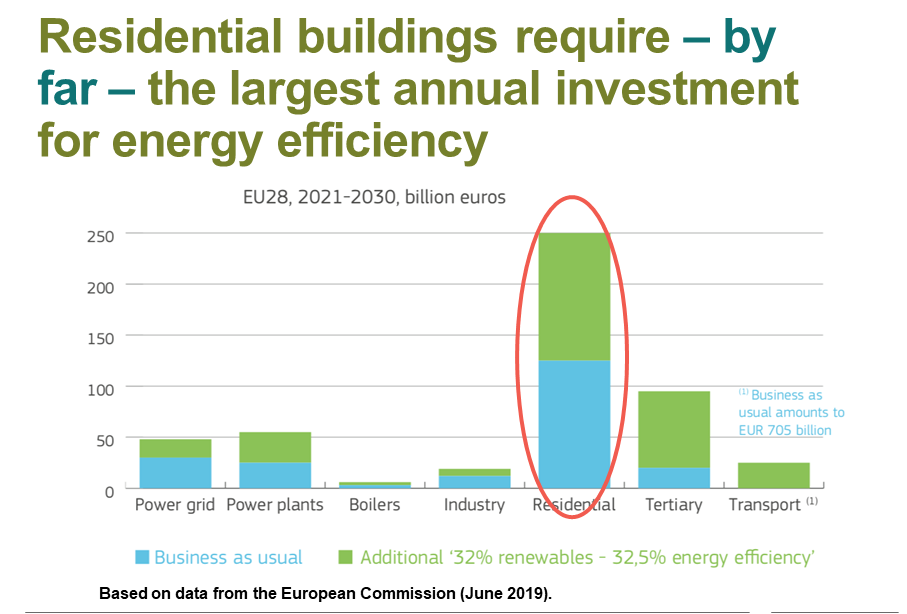

Within the EU context and existing 2030 energy savings targets, Renovate Europe notes an annual investment gap of €130-200 bn. Some 80% of the investment is needed on the demand side, of which 71% must be directed to the residential sector. Over the longer term – i.e. to 2050 – boosting the energy renovation rate to 3% annually would achieve the ambitious goal of reducing energy demand in buildings by 80% while drastically cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. In turn, this would cut total EU energy demand by 30%, reduce energy bills for all consumers, enhance productivity and increase property value and rentals. Such benefits could boost GDP by 0.7% annually; in 2020 alone, that would equal €39 bn in additional public finances.

Boosting the energy renovation rate by 3% annually could, by 2050, lead to an 80% reduction in energy demand from EU buildings. Photo: zazamaza

Renovate Europe calls upon EU institutions to ensure that the European Green Deal creates the ecosystem for deep energy renovation, including establishing stability that will eliminate the current ‘stop-go’ dynamic that erodes investor confidence. This includes making energy efficiency a top priority and planning beyond short-term measures.

While this briefing focuses on the leveraging funds through the Just Transition Mechanism and carbon revenues, an upcoming complementary briefing will examine the need for strong policy, the potential of public-private partnerships, and the particular challenges of financing renovation in the residential sector.

Ensuring energy efficiency builds fairness into the Just Transition

The ambition of the European Green Deal is reflected not only in the scale of its targets but in the fact that they are to be achieved while balancing social, economic and environmental challenges. The commitment to ensure ‘no one is left behind’ is a monumental shift. Among other aims, these targets are designed to stimulate implementation of national renovation strategies.

The experience of the EU 20/20/20 targets is useful in relation to assessing the scale of funding needed as well as for the lessons learned about how to stimulate use of available funds, including to leverage private and public investment. When speaking of energy efficiency, the business case for using lower energy bills to re-pay loans for building renovations has been well-known for the past 10 years – but, it is not being taken up.

With the European Green Deal, the Just Transition Mechanism aims to facilitate bold policies, bold action and bold investment. But experience shows this will not happen without roll-out of innovative financing models that combine subsidies, grants, guarantees and loans within effective policy and regulation frameworks. The Mechanism seeks to address two overarching shortcomings of past plans:

Electoral barriers: The Mechanism acknowledges the disconnect that the European Green Deal is setting out 30-year strategies against electoral cycles that are typically 4-5 years, which make it very difficult for any government or party to ‘sell’ a renovation platform that will incur large public debt through to 2050.

Projects are not always financially feasible: The Mechanism takes into consideration that energy renovations are often feasible for businesses, but not for individual homeowners, in which case the need to have work done and to access financing is extremely granular. It also accounts for the reality that wide-scale renovations may not be feasible for Member States (MS).

Sustaining support for the long-term goals of the European Green Deal will be a challenge across the 4-5 year election cycles at EU and Member State levels. Photo: netivist.org

The Mechanism aims to deliver benefits to all segments of society. A key tool in this regard is the Just Transition Platform, which is designed to provide technical assistance to MS and investors and, in turn, ensure the involvement of affected communities, local authorities, social partners and non-governmental organisations

The Mechanism is built upon financial engineering principles that aim to mobilise – from public and private sources – up to €100 bn over the period 2021-27. At their core, these principles aim to reduce risks. This is because involving private sector money, which can more easily participate in the ‘risk-reward’ world, is critical. The reality is that MS governments facing the biggest challenges in the Transition are also the most likely to be constrained from taking on more public debt. They may simply have different priorities for debt, be overburdened by existing debt or want to avoid surpassing acceptable levels. Additionally, they may want to stay away from the pressure of financial markets.

In relation to energy efficiency and buildings renovation, the Mechanism moves beyond ‘loans for buildings’ in that it aims to capitalise on the ways that building renovations can renovate economic activity more broadly.

Pillars of the Just Transition Mechanism

In name, the Just Transition Mechanism defines a key aspect of its scope: while all MS are eligible to access the Fund, it targets those MS and regions most affected by the transition, including facing higher costs. It will prioritise funding to MS that have the highest carbon-intensity economies and the most people working in fossil fuel sectors. Importantly, the Mechanism is not designed to save ‘dying’ industries (such as fossil fuels) but to stimulate new ones across diverse sectors such infrastructure, technology, energy, buildings, etc.

The Mechanism is strategic on the lending side in that it comprises three pillars designed to tackle different financing challenges and stimulate different types of co-investment by public or private partners. In turn, it is strategic on the receiving side in that eligible MS must submit Transitional Plans that carefully itemise all measures they intend to take. The Commission and the MS will assess these plans and allocate funding accordingly. The three pillars are as follows:

Just Transition Fund: With a base of €7.5 bn from the Commission, this fund aims to generate €30-50 bn in investment. Its purpose is to ‘alleviate the cost of the transition’, along two main policy streams: the economic stream focuses on diversification while the social stream targets re-skilling of workers. This combination seeks to ensure that sectors affected, as well as jobs lost, in the transition will be recreated in other/new sectors to maintain overall economic activity – and that MS have enough skilled workers to fill such jobs. To tap into the Fund, MS will have to commit to match each euro from the Just Transition Fund with money from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund Plus, as well as provide additional national resources as required under the Cohesion policy.

While all types of projects are eligible, the case for energy renovations would be strengthened by linking them to alleviating the cost of the transition. A MS or region that depends heavily on coal for heating, for example, might present that, in parallel with phasing out coal mining and coal-fired power generation, financing buildings renovation alleviates the cost of transitioning to new energy sources or lowers overall energy demand (ergo, also lowering overall costs).

Invest EU: Targeting €45 bn of investment mobilised, this funding is available across four areas: sustainable infrastructure; research, innovation and digitalisation; small and medium-sized business; and social investment and skills. Energy efficiency projects would most likely fit within the first area, but there may be scope to secure support for research, innovation and digitalisation. All projects must be shown to be ‘bankable’, having some sort of revenue to deliver a return on investment.

Public sector loan facility: With a contribution from the EU Budget of €1.5 bn, this new instrument is intended to leverage €10 bn of loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB) such that they mobilise €25-30 bn in total. The combination of a either a grant or an interest rate subsidy plus an EIB loan will make it easier to engage national authorities.

In November 2019, the EIB announced that its new lending policy would, in essence, transform it into a climate bank and establish a green projects fund. This loan facility thus fits well with the EIB’s new mandate. It is anticipated that projects such as energy efficiency, district heating and renewable energy infrastructure are likely to be eligible. The Commission will table the full proposal for this instrument by the end of March 2020.

High carbon-intensive economies present a challenge, but the ‘Just Transition Mechanism’ will help to ensure the involvement of all Member States. Photo: acilo

Again, while all MS are eligible to the Just Transition Mechanism, there is one element of conditionality: to access funding under Pillars 2 and 3, a MS (or region) would also have to apply for funding under Pillar 1. One way in which MS less affected by the transition might qualify is to participate in a regional activity in which multiple MS collaborate to alleviate the cost for some partners.

Some may be quick to point out that, in relation to the scale of funding needed, the Just Transition Mechanism falls short. But readers should not underestimate the substantial investment it represents.

Maximising the impact of carbon revenues through energy efficiency

While the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) has been in place since 2005, the expectation that carbon prices will rise in the future creates potential for it to become a new source of substantial funds. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Maximiser project estimates that by 2030, the EU ETS could deliver revenues of €200 bn to MS.[1]

Pricing carbon aims to stimulate action to reduce emissions in two ways. First, through price signals that prompt a ‘demand response’; by increasing the overall price consumers pay for carbon-intensive energy, the argument is that they will have incentive to use less (or be more conscientious about energy use). In the power sector – so far, the most important sector covered by the EU ETS – the second, more systemic incentive of carbon pricing is to drive change in the dispatch order of power generation, such that the extra cost to fossil-fuel plants makes their bids higher and lower-priced, cleaner power generation will be selected earlier in the supply mix. Depending on the carbon price and the types of power plants in a given power market, this impact on dispatch – the so-called ‘merit order effect’ – can have either moderate or negligible impacts on emissions. Unless lower-emitting resources are actually available to be run more often and carbon prices are high enough to prompt their use, the impact on dispatch is often rather low. A more direct route to emission reductions is needed, especially in the buildings sector.

The introduction of new carbon taxes and carbon prices is challenging and struggles to gain public support in many areas, as the cost of the schemes are passed on to consumers through the cost of energy. With the carbon price in the EU ETS currently low – at around €20 – the reality is that across European power systems, carbon reduction can carry a cost for consumers as high as €248 per tonne avoided.[2] It is well known that power markets magnify the consumer cost of carbon prices, because increased fossil prices drive up the clearing price in the wholesale market for all power in the mix.

Box 1 • What makes emissions abatement costly in power markets?

The current structure of electricity markets – and particularly how supply is chosen to balance with demand – has a huge impact on the cost of reducing CO2.

In single price electricity wholesale markets, generators bid in to supply a portion of anticipated demand. The lowest cost generator is selected first, then the system operator moves up the price scale as needed to deliver against total projected demand for that period. The last generator selected is the most expensive and, in today’s markets, is usually fossil-fuel based. Known as the ‘clearing generator’, this supplier sets the price for all generation in the mix at a given time.

At present, it is the CO2 emissions of the clearing generator that determine the relevant carbon price; however, that carbon price gets added to the clearing price for all generation. As a result, consumers end up paying the carbon price on all megawatt hours (MWh) in the mix, not just the supply generated by carbon-intensive suppliers.

At €20/t, however, carbon prices are not effective on either of the intended aims. The degree to which consumers reduce use in response to the price signal is very low and only limited shifts have been noted in dispatch order.

Given that passing the costs associated with CO2 emissions on to both producers and consumers is a core element of carbon pricing, it effectively raises the value of units of carbon-intensive energy that don’t need to be produced or consumed. In this regard, using carbon revenues to support investment in energy efficiency renovations is a straightforward way to buffer the costs. In fact, a recent study by the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP), based on evidence from Europe and abroad, shows that directing carbon revenues to energy efficiency saves 7-9 times more carbon than price mechanisms alone, while also delivering other benefits (Figure 1).[3] Data from the European Commission show that the greatest need for energy efficiency renovations is - by far - in the residential sector (Figure 2).

Figure 1 • Cumulative carbon emissions reduction with 3% rise in rates only versus 3% rise + directing funds to energy efficiency. Source: Regulatory Assistance Project (2015)

Figure 2 • To reach the EGD goals of 32% renewables and 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency, the EU must get serious about renovating people’s homes.

Additionally, investment in improving the energy performance of buildings can offset current regressive forms of revenue generation – i.e. taxes on energy bills – that have higher impacts on low-income households. Taxes calculated as a percentage of income and expenditures clearly place a much heavier burden on such households.

At least three MS have programmes that link carbon pricing to energy efficiency. Germany dedicates KfW loans to such projects while in France, the Association national de l’habitat (ANAH) targets renovations of low-income households.

One stand-out example, which could be replicated within the roll-out of the European Green Deal, comes from the Czech Republic, where a 2012 law requires that at least 50% of carbon revenues be devoted to measures that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Czech scheme directs half of the recycled revenues toward the New Green Savings Scheme, a building renovation programme recognised to be among the most cost-effective energy saving schemes across all sectors in the country.

Over the period 2014-18, this programme distributed €350 m for the energy renovation of over 32 000 dwellings. These subsidies, offered to households to undertake renovations, achieved a leverage factor of about 1:3, with each euro invested by the State attracting a further three euros of private (householder) investment. If this 1:3 return were to be sustained and 100% of national revenues were to be recycled into the scheme, by 2030 in the Czech Republic alone, EU ETS revenues of €4-7 bn could deliver €12-21 bn of investment in renovation.

Revenues from the EU European Trading System can help fund necessary energy renovations. Photo: 49pauly

An evaluation of the broader benefits of these investments found that for each €1 m of State investment, a return to public budgets of €0.97-1.21 m accrued through income tax paid by companies and their employees, lower costs to social and health insurance, and reduced payout of unemployment benefits. In parallel, the expenditure induced GDP growth of between €2.13 and 3.39 m.

Ultimately, the evaluation shows that all of these benefits to public budgets and the economy were achieved while reducing CO2 emissions far beyond what could have been done by using the same money to abate CO2 in power markets.

If similar programmes were rolled out across the EU as part of the Renovation Wave, the impacts would be exponential.

Conclusion

The ambition of the European Green Deal may have taken some by surprise; in fact, they may believe that the ambition cannot be achieved because finding adequate financial resources is impossible. As this article shows, there are innovative ways to finance elements of the European Green Deal – such as the Renovation Wave – that will simultaneously help it succeed and spread benefits to society at large.

This brief was produced in cooperation with Renovate Europe.

(Part 1 of 4) Buildings renovation and the EU Green Deal: http://www.coldathome.today/benefits-of-deep-energy-renovation

(Part 2 of 4) Proof of how buildings renovation can help meet the European Green Deal: http://www.coldathome.today/proof-of-how-buildings-renovation-can-help-meet-the-european-green-deal

(Part 3 of 4) Financing deep energy renovation: leveraging the Just Transition Mechanism and carbon revenues: http://www.coldathome.today/financing-deep-energy-renovation-leveraging-the-just-transition-mechanism-and-carbon-revenues

(Part 4 of 4) Financing deep energy renovation: policy action, public-private partnerships and financial tools: http://www.coldathome.today/financing-energy-renovation-policy-partnerships-and-tools-for-private-dwellings

[1]https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57050297356fb0e173a11732/t/5857dded37c5813a24c54aba/1482153489075/MaxiMiseR+ETS+full+technical+report_FINAL.pdf

[2] www.raponline.org/knowledge-center/carbon-caps-and-efficiency-resources-launching-a-virtuous-circle-for-europe/

[3] www.raponline.org/knowledge-center/carbon-caps-and-efficiency-resources-launching-a-virtuous-circle-for-europe/

https://www.renovateeurope.eu/communications/briefings/